Cathy Davis: The Big White Hype – 1979

By Jack Newfield – Published November 1979 – Volume. One – Originally printed in the VOICE

Vol. XXIII No. 41 “The Weekly Newspaper of New York, October 16, 1978

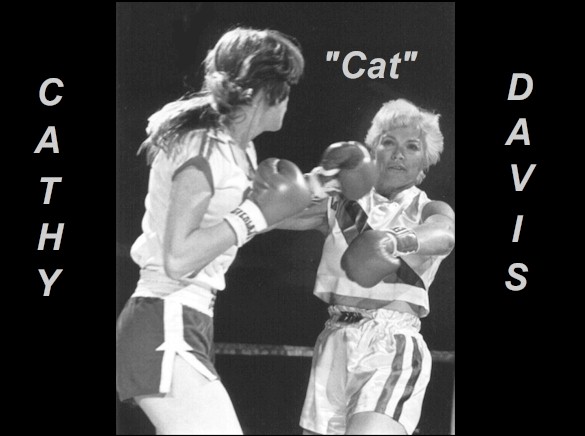

Cat Davis is a kinky media phenomenon, a product of the Great American Hype Machine, just like Tiny Tim or Jerry Rubin. She has been profiled by People magazine. She has been interviewed on the Today Show. She participated in the Superstars, a trash sports show on ABC-TV, Cat is a lady boxer who is white, blonde, and pretty.

Cat is also not what she appears to be. And her manager-boyfriend, Sal Algieri, stands accused of trying to fix her fights, of controlling a fake “commission” that regulates women’s boxing, and of using phony names for her opponents. When Algieri boxed professionally himself, 15 years ago, he admitted throwing a fight.

Moreover, Davis’s last bout—staged June 7, 1978 in Georgia, a state that has no boxing commission— was apparently promoted by her own lawyer—an unethical conflict of interest. Cat’s opponent, a “gym rat” from Chicago named Ernestine Jones, says she was told by Algieri to lose, but, instead, she knocked Cat out. Jones is a black woman.

Ernestine’s purse was a $535 check made out to her manager. Payment on the check was stopped by the fight’s promoters, Robin Suttenberg, who was Cat’s lawyer at the time. Robin claims she was not “the actual promoter,” that the actual promoter was Arthur Appleman, under the name Pyramid Promotions. Arthur Appleman is a lawyer who happens to share the same office, room 1066 at 233 Broadway, with Robin Suttenberg. Appleman admits that he and Suttenberg “are very close friends.” He admits Robin signed the canceled check for Pyramid Promotions but insists that she “has no legal connection to Pyramid Promotions. I am the only officer and director.

But the incorporation papers on file with the state list Suttenberg’s name as the lawyer. Robin Suttenberg says she represented Cat Davis for two years working on a lawsuit that ended in victory last week, when the New York State Athletic Commission grated Cat Davis a license to box in this state. But Suttenberg told me this week: “I am no longer Cat Davis’s attorney.”

Why would she withdraw at the moment of triumph?

“Algieri and Cat never never paid me. They owe me my fee. And I can’t find them. They don’t have a phone. “They don’t have a phone because they never paid the phone company either.

Cat Davis and Sal Algieri have a good scam going. Using the rhetoric of women’s rights they think they are going to get rich. Algiera says he is negotiating a three-fight television contract with a network, worth hundreds of thousands of dollars. He says a Westchester promoter is offering him a lot of money for a bout in December. On September 20, the day after the athletic commission gave Cat her license, her picture was in the Metro, the Daily Press, and the News World, and all three papers reported she was undefeated. In the Metro, Steve Serby, football writer for the New York P ost, described Algieri as “a former North American welterweight champion.”

The official records of the New York State athletic commission show that Algieri had six professional fights, of which he lost five, including his admitted fix.

Serby also quoted Algieri as saying he spent “more than $8000 in court fees,” which is news to lawyer Suttenberg.

The same day that Cat Davis got her license, two black women also got licenses to box—Tyger Trimiar and Jackie Tonawanda. Cat’s skills are now open to question. Trimiar and Tonawanda have authentic talents, but they are black and have not been invited to be photographed by People magazine, or box in Westchester in December. Or even get their picture on the cover of Ring magazine, as Cat did last month. (The story was under Algieri’s byline.” Like the great black male fighters of other eras, from Peter Jackson, who John L. Sullivan ducked, to Sam Langford and Harry Wills, who Jack Dempsey would never face, they are less marketable, and less equal.

Also, Trimiar and Tonawanda first applied for licenses two years before Cat Davis but with much less publicity. Tonawanda’s lawyer, Stanley Solomone, says Cat’s lawyer, “just copied my (legal) papers.”

CAT’S LAST BOUT

The Cat Davis/Ernestine Jones fight in Atlanta was a one-sided mismatch. Jones knocked Davis down five times and the contest was stopped at the end of the third round. After the fight, in the dressing room, Algieri made various complaints and alibis. He said Cat was sick and drugged. He said her opponent should have been disqualified for pushing. But, to her credit, Cat Davis said: “Don’t make excuses, Sal. I lost. It was a fair fight, and I lost. Don’t make excuses.”

But Algieri saw all that money going down the drain, all the television offers for his “undefeated” product vanishing. He had to do something to salvage his gimmick.

Five days after the fight, Jack Cowen got a telegram in Chicago. Cowen, a respected boxing veteran, is the manager of Ernestine Jones. The telegram said that the result of the fight was officially being changed to “no contest” because of dirty tactics, and that Cowen, “Connie Smith,” and trainer Randy Tidwill were being “suspended for six months.” The telegram was signed by Al Gallello, “chairman of the Women’s Boxing Federation.”

The Women’s Boxing Federation exists only on a letterhead and a post-office box. The WBF letterhead also lists Sal Algieri as an “adviser.” Until recently, the WBF and Algieri shared the same post-office-box address in Lodi, New Jersey. Boxing Illustrated magazine refuses to publish WBF “ratings” because they are phony. And Al Gallello is a close friend of Algieri’s according to athletic commission records, he was Algieri’s manager 15 years ago. The WBF is a flagrant front and is not recognized as having any legitimate standing by the New York State Athletic Commission.

Jack Cowen was naturally furious that Algieri was trying to tamper with the legitimate result of the June 7 bout. And, on August 25, 1978, Cowen gave a notarized affidavit to the New York State Athletic Commission. The affidavit says, in part:

“Two days prior to the fight, Mr. Algieri made several attempts to myself and Randy Tidwell for Ms. Jones to lose the bout, stating she “had to lose” in order that Mr. Algier’s television arrangements would not be affected by a loss. Mr. Algieri also stated that if Ms. Jones lost, it would mean a television appearance by one of our other female boxers.”

Cowen has also told the New York commission that he was instructed by Algieri to give Jones the name of “Connie Smith” for the Atlanta bout. The Atlanta papers and the wire services did report that “Connie Smith” defeated Davis that night. The real Jones who knocked Cat out had only had one professional fight before, and she had lost it. Cowen thinks he was asked to use the name “Connie Smith” because there was another female boxer by that name, and it would look better on Cat’s record.

ENTER FLASH GORDON

This whole cynical, Marx Brothers version of Frankie Carbo was exposed by Flash Gordon. There are dozens of paid, professional sportswriters in New York City. But not one of them took the time to look behind the hype of Cat Davis. Some of them even went along with it, thinking it was “good copy.” But not Flash, the Tom Paine of the sweet science.

Flash writes and distributes his own mimeographed boxing newsletter and program from his low-rent apartment in Sunnyside, Queens. He buys all the out-of-town papers for the fight results and keeps the most accurate career records on boxers. It was Flash who first revealed the phony records used by the fighters in the now disgraced Don King ABC tournament last year.

Flash, who looks like a ‘60’s hippie freak, can usually be seen outside Madison Square Garden on fight nights selling his program. His newsletter is informative and distinguished by a passion to expose the dishonest elements of boxing. Flash will not talk to professional sportswriters because he thinks they are all on the take. Flash will not accept free press tickets from promoters to preserver his own independence; he buys the cheapest seats for fights and watches them through binoculars.

In his June 29 newsletter, Flash wrote:

“An outrageous and crooked scenario to defraud, by a gang of rat like “Loony Tune” characters from the New York-New Jersey area, has been uncovered by this program. After handling many complaints from various managers across the United States, we feel it’s’ time the antics–—rest comical, yet now which have turned to theft, swindle, and racketeering, must be made public to save future suckers from entering the same trap with the ‘cheese,’ namely their money on the line, and/or boxers.” (Ron Rapoport, the Chicago sportswriter, has also written an excellent expose of Algieri’s racket.”

Flash went on the reveal that most of Cat Davis’s opponents have boxed under phony names, and that Cat has “knocked out” the same opponent four times under different names. Flash also pointed out that women’s boxing in California and Nevada is legitimate, competitive, and different from what he calls Sal Algieri’s “dive caravan.”

SAL ALGIERI’S FIXED FIGHT

Last week, when Cat Davis got her boxing license from the athletic commission, Sal Algieri expected to pick up his manager’s license at the same time. But Algieri did not get it because the commission is now investigating his conduct when he was a professional boxer in the early 1960s.

On November 26, 1962, Sal was knocked out by Rocky Gattelari in Sydney, Australia. After the fight Algieri admitted he lost on purpose. On December 19, 1962, Algieri was questioned by the New York Athletic Commission about his dive. The transcript of that session still exists in the files of the commission, and I read it this week. In it, Algieri admits that he agreed before the bout to lose in the second round.

In the interview Algieri also admits that his various claims of being a former Golden Gloves champion, of being “the New York state bantamweight champion” are totally false. Question: “You are a four-round $50 fighter, is that correct?”

Algieri: “That’s right.”

Algieri also admits his true professional record is five defeats and one victory. He never boxed again after this interview.

The athletic commission has had one other prior contact with Algieri. In 1976, he picked up an application for a license and gave the commission a five-dollar check. The check bounced.

Sal Algieri says Cat will box on December 6, at the White Plains County Center. The state athletic commission, however, which is doing an excellent job protecting the ticket-buying public, will look very closely at the name, record, and management of any prospective opponent. Also, the commission is not going to license Algieri until the investigation into his background is complete. And it is possible boxing fans won’t pay to see Algieri’s “dive caravan.” Only 200 people bought tickets to the Atlanta bout, and Pyramid Promotions lost $9000 on the fiasco. Jack Cowen has gone to the FBI, and that agency is now investigating Algieri under the Interstate Transportation to Aid Racketeering statute of the criminal code. Meanwhile, Ernestine Jones, who is black, poor, and still unpaid, is training in Chicago and hoping for work.